An imminent court case could be an important step toward enshrining environmental rights in Canada's constitution. Original Creative Commons photo by Flickr user EuroMagic.

Over the last 40 years, 90 countries have amended their constitutions to include the right to a healthy environment. Portugal was the first in 1976, and since then scores have followed, from Argentina to Zambia. But not Canada.

What we have is the 1999 Canadian Environmental Protection Act. Under that law, polluters found in violation can be fined up to $1 million a day, sentenced to three years in jail, or both. Unfortunately, CEPA’s overall efficacy is dubious. Consider environmental lawyer and author David R. Boyd’s comparison: fines levied under CEPA from 1988 to 2005 totalled $2,224,302; in 2009, the Toronto Public Library collected $2,685,067 in overdue book fines. “It is absolutely vital for us in the years ahead to amend our constitution to reflect the right to a healthy environment,” says Boyd. Doing so prompts many notable environmental improvements and, better yet, allows people to hold governments accountable—that’s key considering who most often suffers environmental burdens.

Take Sarnia, home of the Aamjiwnaang First Nation. Canada’s first oil refinery opened there around 1871. Today, Sarnia is home to 40 percent of Canada’s petrochemical industrial operations. Within 25 kilometres of the Aamjiwnaang reserve, there are more than 60 industrial facilities, about 46 of them on the Canadian side of the border. Among these are three of the top 10 air polluters in Ontario. In 2005, these facilities emitted almost 132,000 tonnes of air pollutants.

“If people had a constitutional right to live in a healthy environment,” says Boyd, “a government or court would have stood up and said it is unjust to continue piling pollution onto these people.” Instead, in 2010, two members of Sarnia’s Aamjiwnaang First Nation launched a lawsuit against Ontario’s Ministry of the Environment; the case goes to court next year. The two members of the Aamjiwnaang assert that by permitting a recent 25 percent increase in production at a Suncor refinery, the government has violated Section 7 of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms: the right to life, liberty and the security of the person. Lawyers also cite a violation of equality rights under Section 15 of the Charter, saying the Aamjiwnaang bear a disproportionate environmental burden.

However, according to Ecojustice lawyer Justin Duncan, who is arguing the case, if the constitutional right to a healthy environment already existed, “we would be arguing about the amount of pollution and comparing that to existing laws.” In other words, without an explicit constitutional right, it takes judicial gymnastics to justify environmental protection. Responsibilities also remain ambiguous, Duncan adds, making it difficult to enforce regulations or respond to modern environmental challenges. Talk about murky waters.

]]>Many First Nations citizens see their tax-exempt status as a function of the treaties and other legal arrangements with the Crown, or as partial compensation for the resources taken from the lands. They believe that imposing an income tax would be not only unfair, but unconstitutional.

Canada’s courts have upheld tax exemptions as a means to preserve the collective rights of First Nations, ensuring that the Crown does not attempt to erode the reserve land base through taxation.

The federal government has made little effort to explain the policy to Canadians, allowing an unhealthy resentment to grow. There has been little counterpoint to the pressure from the right on this issue. Given the public confusion, it seems a worthwhile exercise to actually do the math and see what light it sheds on the matter.

First, it helps to be specific about whom we are talking. Income is only exempt from tax when earned by status Indians working on reserves. The 2006 census identified fewer than 700,000 people who have a North American Indian identity. This number includes about 133,000 who are non-status Indians and slightly more than 565,000 status Indians who might be exempted from paying income tax, if they earned income on-reserve. Bearing in mind that half of Aboriginal people are under 20, more than 40 per cent of status Indians live off-reserve, and Aboriginal people have an unemployment rate more than twice the national average, it is not surprising that the number of people exempted from paying taxes is actually quite small. In fact, the most recent figures tell us that the number of First Nations citizens living on reserves who had employment or self-employment income was only 103,885.

Unfortunately, Statistics Canada has not made average income numbers for on-reserve employment freely available—which would have allowed for a more precise calculation—but we do know that the median income is $13,637. This allows us to estimate the total employment and self-employment income earned on-reserve as somewhere in the neighbourhood of $1.4 billion.

So what is the total of tax revenues lost to Canada as a result of the exemption?

The federal income tax rate for those earning less than $41,544 is 15 percent. Provincial tax rates vary, but adding them into the calculation puts the tax rate somewhere between 20 and 25 percent across the country. The basic personal deduction is $10,382, which would leave just over $4,000 in taxable income from the median, even with no other deductions. On that amount, one would owe between $800 and $1,000. Multiplying that back out against the 103,885 earners, the exemption amounts to between $84 million and $104 million in foregone revenues.

If all of those earning income on-reserve actually qualify for the exemption, the Receiver General is collecting approximately $100 million less in taxes as a result.

It is possible to quibble with the figures here. I have used the most recent census figures from 2006 with the 2010 tax rates and using the median income level rather than the average leads to a lower total. Nonetheless, even the highest mark-ups on all of this data wouldn’t put the lost revenue higher than $120 million.

That number is nothing to sneeze at, of course. But in the context of a 2010 budget of more than $261 billion, it’s also not going to make or break the federal government. Nor does it seem disproportional or unfair, when looked at in context. By way of comparison, there are $1.4 billion in annual subsidies for oil and gas companies, equivalent to the total income earned on-reserve, and $120 million in subsidies for ethanol production, equivalent to the highest estimation of revenues lost to the Canadian government through the income tax exemption.

More to the point, the tax exemption in no way compensates for shortfalls in funding to First Nations. The provinces spend more than 20 percent more on children than the federal government does on First Nations children, whether those kids are in school or under child welfare services care. The disadvantage to First Nations children from these two policies alone amounts to far more than the foregone tax revenues, and there are dozens of other examples.

Taxes pay for public services like roads and water, and First Nations communities are notoriously under-serviced. A 2005 study by the Assembly of First Nations found that, per capita federal funding for First Nations citizens is $7,200. That’s far lower than the amount that the government spends on the population in general. In Ottawa, for instance, the combined per capita spending by all three levels of government totalled $14,900, more than double the amount being spent on-reserve.

Given the amount of energy certain groups have spent decrying this tax exemption, one might have expected them to conduct an analysis of this nature. The fact that they haven’t might suggest that there is another agenda at work in their complaints.

The balance of advantage is clear when the tax exemption is compared to the lack of services on-reserve. To whom is the system unfair when the numbers are so grossly tilted the other way? And why focus on this issue when there is so much else that needs to be done?

Recalling the views of the Supreme Court, if First Nations land can be eroded through tax policy, it is an efficient way to end communal land ownership in Canada. Once that is accomplished, First Nations can be fully assimilated into the mainstream and any resources on or near their lands can be exploited without the inconvenience of consultation or compensation. Complaining about tax policy is only one of many ways in which the right wing in Canada is seeking to achieve that goal.

Pierre Trudeau. Bill C-150, passed by his government on May 15, 1969, ushered in a new era of human rights in Canada.

Tomorrow, let’s take a moment to reflect on the 42nd anniversary of the passing of Bill C-150, the omnibus bill that decriminalized abortion, contraception and homosexuality. The rights that Canadians have because of this historic bill are crucial to remember as those same rights come under attack elsewhere: on Wednesday, Indiana became the first state in the U.S. to cut public funding to Planned Parenthood. The same day in Uganda, gay people came close to facing the death penalty.

On May 14, 1969, The Criminal Law Amendment Act formed the legal foundations for the Canadian gay rights movement, and for Henry Morgentaler to perform abortions against — and eventually according to — the law. But it didn’t reduce discrimination, or grant women and members of the LGBTQ community full rights under the charter. Forty-two years later, how much has changed?

Abortion and contraception then:

In the 1950s, a family of five was considered small, explained former nurse Lucie Pepin in her speech commemorating the 30th anniversary of Bill C-150. Many women in rural communities gave birth to their children at home. When complications occurred during birth, the mother was rushed to hospital. If it was too late for a cesarian, her doctor had a decision to make:

“Which to save — the baby or the mother? The Church was clear: save the baby. The Church was clear on many points — women sinned if they refused sexual relations with their husbands or any other form of contraception. The State was also clear. Contraception was illegal and so was abortion.”

Women had no choice in the matter, and neither did their doctors. But Bill C-150 at least changed the latter. The legislation decreed abortion was permissible if a committee of three doctors felt the pregnancy endangered the mental, emotional or physical well-being of the mother. Regard was not given just yet to women’s charter rights to life, liberty and security of the person.

Enter Henry Morgentaler. In 1969, armed with decisive arguments in favour of a woman’s right to an abortion within the first three months of pregnancy, the doctor began performing the procedure illegally in his Montreal clinic. An exchange in 1970 between the adamant doctor and a furious caller on CBC Radio highlighted the fundamental disagreement between the doctor and his critics about when life begins.

Now:

The debate hasn’t progressed. It has degenerated into little more than a shouting match between so-called “pro-life” and “pro-choice” advocates who still can’t agree on when life begins, or whose rights win out: those of the mother or those of the unborn fetus. And recently the Canadian debate has shifted for the worse.

In Indiana, the governor was quite happy to openly chop away at Planned Parenthood’s $2 million in public funding. Meanwhile, in Canada, subtler shifts are taking place. During the election, Tory MP Brad Trost bragged that the Conservative government had successfully cut funding to Planned Parenthood. Stephen Harper quickly denied the comments, saying he would not re-open the abortion debate as long as he is Prime Minister. However, the International Planned Parenthood Federation has been waiting for 18 months to hear whether their funding from the Canadian government will be renewed. During the election, women’s rights groups foreshadowed the Conservatives’ indecision on the matter warning Canadians that Harper would be under pressure from his caucus to re-open the debate. With a Conservative majority now in government, that pressure is sure to grow.

Homosexuality then:

149 Members of Parliament agreed with Trudeau and 55 did not after he famously said “there is no place for the state in the bedrooms of the nation.” According to his omnibus bill, acts of homosexual sex committed in private between consenting adults would no longer be prosecuted. But gay sex between people younger than 21 was still illegal.

A Gallup Poll at the time that asked Canadians whether they thought homosexual sex should be legal or illegal found 42 percent in favour of decriminalization and 41 percent against. Homosexuality was openly discussed as an “illness” that ought to be cured. Progressive Conservative Justice Critic Eldon Woolliams voted in favour of Trudeau’s bill so that gays could have the equal opportunity to receive treatment. On February 2, 1969, he said casually on CBC television:

“I don’t think (homosexuality) should ever be put in the criminal code. I think it should be taken out. It should be done in a medical way so that these people could be sent to centres if we feel as citizens who oppose the feeling of this illness and this homosexuality so they could be rehabilitated.”

Woolliams appeared to sincerely (and incorrectly) believe that gay sex was a mere tendency based on environmental factors, and that the “pressure” of these factors could be “relieved.”

Before Bill C-150 was passed, “incurable” homosexual George Klippert was convicted of “gross indecency.” He was sentenced to preventative detention. In 1967, the Supreme Court upheld the decision.

Now:

Today the Ugandaan Parliament debated a bill that aimed to punish “aggravated homosexuality” by increasing jail sentences from 14 years to life. Until yesterday, the bill also proposed the death penalty for gays. The main motivation behind the legislation was preventing the spread of HIV and AIDS.

We would like to think that Canada is 40 years ahead of Uganda, but we still impose discriminatory policies to prevent the spread of what used to be known as “the gay cancer” — HIV/AIDS.

The policy of the Canadian Blood Services is to ban any man who has had sex with another man since 1977 from giving blood for the rest of his life. The organization asserts that it is arms-length enough from the government to uphold the ban without fear of violating Charter rights. The CBS also discriminates based on action rather than sexuality — a gay man who hasn’t had sex is welcome to give blood. A third argument holds the least strength: though HIV/AIDS testing has advanced over the years, the possibility of a false negative still exists.

However, the policy is inherently discriminatory because it assumes any man who has sex with another man carries a high possibility of illness despite other factors such as relationship status, use of condoms, and differing risk factors based on oral versus anal sex. The CBS, which is regulated by Health Canada, maintains its policy based on outdated science. To their credit, the organization has offered a grant of $500,000 to any researcher(s) who can find a safe way to allow “MSM” men to safely give blood. No researchers have applied for the grant.

The lifetime ban is outdated, as is the recommended deferral period of 10 years, which the U.K. recently implemented. Australia, Sweden and Japan currently have deferral periods of one year. Researchers for the Canadian Medical Association Journal have recommended a one-year deferral policy for MSM donors in stable, monogamous relationships.

We’ve progressed, but we’re not perfect. And there’s a real risk of losing what we have. On May 14, let’s be grateful to the activists that pushed the LGBTQ and women’s rights movements forward.

]]> It’s time for a little refresher course in Canadian civil society: Canada’s formal political dependence on Britain came to an end in 1982 with Pierre Trudeau’s Canada Act. The Act led to the patriation of the Canadian Constitution–you know, that old document that outlines the vibrant democratic system of government we so proudly employ in Canada (well, at least those 59.1 percent of us who voted in our last Federal election anyhow). Entrenched in our Constitution is a document that affects everyone in Canada, even those who choose not to vote: the Charter of Rights and Freedoms.

It’s time for a little refresher course in Canadian civil society: Canada’s formal political dependence on Britain came to an end in 1982 with Pierre Trudeau’s Canada Act. The Act led to the patriation of the Canadian Constitution–you know, that old document that outlines the vibrant democratic system of government we so proudly employ in Canada (well, at least those 59.1 percent of us who voted in our last Federal election anyhow). Entrenched in our Constitution is a document that affects everyone in Canada, even those who choose not to vote: the Charter of Rights and Freedoms.

The Charter represents the cornerstone of Canadian civil society: it proscribes the democratic, legal, equality and language rights that, together, make up the freedoms we enjoy. It is the bill of rights that guarantees all of the civil and political rights that make Canadian society the open, free and generally tolerant place (the G20 aside) that it is.

The rights enshrined in the Charter–the right to “life, liberty and security of the person,” among others—are key to Canada’s national self-image, and so you would assume that they would amount to more then a mere trifling concern. Yet the federal government’s failure to repatriate Omar Khadr is reinforcing a lesson hard learned by many Canadians during the G20: our government is entirely capable, and far too willing, to ride roughshod over our rights. And what’s even scarier is the public’s non-reaction to Khadr’s case, which proves just how complacent many Canadians will be while their rights are stripped.

And it is in this respect that the Charter and the rights it enshrines have been forgotten by many within Canadian society–and if not fully forgotten, then perhaps forcefully consigned a safe distance behind a barricade of riot police as our government elevates fear-mongering and ‘security’ over liberty and legality.

Despite numerous rulings from Canada’s courts, including a recent ultimatum from the Supreme Court demanding our government act to protect his rights during the trial or repatriate him for trial in Canada, Toronto-born Khadr is the last remaining Western citizen held at Guantanamo Bay. While all other nations have repatriated their detainees—including England, France and most recently Yemen—Canada remains the holdout.

At question here is not Khadr’s innocence or guilt. Even if we presume the worst of Khadr—that he is indeed guilty of throwing the hand grenade that fatally wounded American medic Christopher Speer in 2002, that he did so unprovoked, willingly and, at the tender age of 15, with complete awareness of his actions and that he is an unrepentant jihadist—his treatment since his arrest would make even those responsible for the Patriot Act blush.

Here are the facts. Khadr has been held for eight years without trial: so much for section 8, 9, 10 and 11 of of the Charter guaranteeing a presumption of innocence until proven guilty, a “fair and public hearing by an independent and impartial tribunal” in a “reasonable time.” A pretrial hearing revealed that his initial questioning at Afghanistan’s Bagram prison occurred while he was shackled to a stretcher following his hospitalization for severe wounds suffered during the fighting and was sedated for pain. His first interrogator, identified in a fittingly Orwellian manner only as “Interrogator One,” was later convicted of detainee abuse in a separate case; he threatened Khadr with gang-rape and death to coerce the 15-year-old suspect into talking. For parts of his interrogation he was hooded and handcuffed with his arms restricted painfully above his shoulders, and he was systematically deprived of sleep before cycles of interrogation. This conduct clearly violates the Charter’s section 12 prohibition on cruel and unusual treatment or punishment.

Khadr’s case represents the first time a Western country will try someone for war crimes allegedly committed as a child since the Second World War, an act that has earned condemnation from the United Nations, Amnesty International, and many others.

The most recent court verdict placed the onus on the Federal Government to protect Khadr’s rights and bring him home; Ottawa, predictably, appealed the verdict knowing full well that with Khadr’s impeding trial set to begin next month they’ve dodged any legal responsibility to act.

So–what are we left with? Well, for one, we’re left with Omar Khadr facing the grim prospect of a military tribunal in the United States with zero support or interest from Ottawa. But more pertinently we’re left with a government who has shown their true nature yet again—they prorogued Parliament when it raised unappealing questions on the Afghan detainee issue, they quashed civil liberties when people took to the streets to demand change, and they rebuffed the Supreme Court and the international community in what is set to be the first case in modern history of a child soldier standing trial.

All these events add up to a gradual erosion of our civil liberties and constitutional rights, and the blithe indifference of so many Canadians is ominous.

]]>

Newspaper photo editors show their creativity when selecting images for this story. Bottom left is from the Star, that actually dispatched a photographer instead of using the file-photo cliché of "eyes peeking through veil"

Quebec is going ahead with its ludicrous ban on religious head-coverings like the niqab and the burka on provincial government property. It’s an astonishing piece of legislation that manages the improbable feat of being baselessly arbitrary and obviously xenophobic. The whole law is crafted to be targeted at a single identifiable—and extremely tiny—minority, but Premier Jean Charest swears up and down that it’s simply intended to ensure that everyone has to show their face to get government services. But everyone understands that the real point of the law is to get a handful of observant muslim women to take off their niqabs—just Google “niqab ban,” and it’s pretty obvious that everyone knows the score. It’s a creepy piece of social engineering, with added bonus dashes of Islamophobia and paternalism.

Constitutional experts called up by newspapers are pretty unanimous in their opinion that this is unconstitional and will be challenged right out of the gate:

“This legislation will probably be considered a breach of human rights,” said Lorraine Weinrib, a leading constitutional expert and professor with the University of Toronto’s law school. […]

By cutting off access to such services to health care and education to women who are following Muslim dress codes, Ms. Weinrib said Quebec is “discriminating” and “disadvantaging” people on the basis of their religion and gender.

“Denying people health care or other government services is such a draconian result, it seems extreme,” she said.

The Law is Cool blog has an extended post today on the niqab law and why it is both legally and ethically untenable. I would encourage you to give it a read — it gives a lengthy primer on some of the core principles of Canadian charter rights, and how they apply specifically in this case. And it goes deeply into the complexities of religious and cultural accommodation: It’s perfectly reasonable to query the religious, social, gender, and cultural dilemmas posed by the niqab. The reasons that some women wear them are numerous and complex—I even believe that quite a few of them are not good reasons, but it’s not up to me.

Cynically, I think the Charest government knows that the law is unconstitutional, and is introducing it to stir the electoral interest of a (depressingly large) segment of society that mistrusts immigrants in general and muslims in particular. There’s nothing like a manufactured bogeyman to spook the base into action.

]]> Among the many responses to a prorogued parliament, we’re tickled by this project from a Toronto small press publisher, Mansfield Press — one that co-stars our own Fiction & Poetry editor, Stuart Ross. He, along with Ottawa’s Stephen Brockwell and Mansfield publisher Denis De Klerck, put out a lightning-fast call for poetry about the proroguement of Parliament, and will publish the book in time for the re-opening of the house on March 3. The details, from Mansfield’s website:

Among the many responses to a prorogued parliament, we’re tickled by this project from a Toronto small press publisher, Mansfield Press — one that co-stars our own Fiction & Poetry editor, Stuart Ross. He, along with Ottawa’s Stephen Brockwell and Mansfield publisher Denis De Klerck, put out a lightning-fast call for poetry about the proroguement of Parliament, and will publish the book in time for the re-opening of the house on March 3. The details, from Mansfield’s website:

Contrary to what the Harper government would have Canadians believe about the “chattering classes,” people are expressing their outrage over Harper’s unilateralism at family dinners, in the workplace, in social media and in print. Professional and aspiring writers across the country have been invited to submit poems for the anthology which will be published by Mansfield Press just in time for the reconvening of Parliament on March 3.

A book launch and protest will be held at or near Parliament Hill on March 5, 2010.

The book will be titled Rogue Stimulus: The Stephen Harper Holiday Anthology for a Prorogued Parliament. We’ll keep you posted on purchasing details as we get closer to publishing day.

]]>Tomorrow is the big day all across Canada, as thousands of Canadians will be gathering to protest Prime Minister Stephen Harper’s decision to prorogue parliament until March 3. There are going to be many ways to participate in this peaceful, non-partisan event, both on the street and online.

This Magazine intern Luke Champion made this helpful Google map, above, which pinpoints the location of all the rallies we could find across the country (and in fact there are several happening outside Canada, too). Click any pin on the map to see the basic details of that event. Details for these are also available through this Facebook event page, and the Facebook group that started this whole ball rolling is here.

We intend to have boots on the ground at several of the rallies to photograph the events and talk to some participants, but we’re a teensy operation. That’s why we’d like your help. Because we just lurve screwing around with new web toys, and ripping off inspired by the pioneering work of our micro-media brethren (ahem), we’ve set up a sweet new Posterous account to aggregate photos, videos, and assorted other media flotsam generated during Saturday’s proceedings. It’s online here: post.this.org

You can easily contribute a photo or a YouTube video or a news link — just email it to:

[email protected]

…and we’ll do the rest (i.e., weeding out the libel and/or porn).

There are 200,000 members of the Facebook group, and buzz for Saturday is promising. But big media outlets have shied away from the anti-prorogue sentiment that has blossomed in the last few weeks, covering it from a distance, running their critical editorials, but always minimizing and hedging the power of digital media — not to mention good old-fashioned pavement-pounding street activism — to drive real change. We hope by collecting, aggregating, and distributing information in this low-friction way, we can prove them wrong. Hope you’ll help us out.

]]>

Historic treaty boundaries between Canada and Aboriginal peoples. Not representative of any proposed outline for an Aboriginal province; vast areas of Canada have never been formally surrendered or ceded by Aboriginal peoples. Courtesy Ministry of Natural Resources. Click to Enlarge

The Royal Proclamation of 1763 included a clause prohibiting British colonists from purchasing “Lands of the Indians,” so as not to commit more of the “Frauds and Abuses” that characterized colonial takeovers of Aboriginal territory. To my reading, this measure was intended to make clear to the English colonists that Aboriginal Peoples enjoyed equal status. As we know, that’s not quite how it worked out.

In 1987, after the premiers met at Meech Lake and agreed to open the Constitution, I proposed to several prominent people involved in the process that the easiest way to respect that commitment, and to lessen the offence of their putting Quebec before Aboriginals, would be to create an 11th province out of the remaining Aboriginal and territorial lands. Twenty-two years later, First Nations are still fighting to get even a modicum of self-government.

When Canada was patriating the Constitution in 1982, Aboriginal leaders were able to create enough domestic and international pressure on the federal and provincial governments that the first ministers committed to making the next round of constitutional change about Aboriginal issues. They even enshrined in the Constitution a requirement for first ministers to have one, and then two more meetings with Aboriginal leaders.

But the election of the Progressive Conservative party under Brian Mulroney in Ottawa, and the defeat of the separatist Parti Québécois in Quebec at the hands of the Liberals under Robert Bourassa, suddenly moved the now infamous “Quebec round” ahead of Aboriginal people. While the constitutional requirement of first ministers’ meetings with Aboriginal leaders to amend the Constitution was met, it seems with hindsight that these meetings were simply pro forma, as Bourassa and Mulroney already had plans for the Meech Lake Constitutional Accord.

The accord failed, in part, due to a single Aboriginal member of the Manitoba legislature named Elijah Harper who refused to give unanimous consent so it could be adopted by the Manitoba legislature by the Mulroney government’s declared deadline for ratification: June 23, 1990.

A year later, the Mulroney government appointed a Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples. Among its recommendations were a list of powers that Aboriginal nations needed to protect their language, religion, culture, and heritage.

The underlying concepts are similar to the powers that the Fathers of Confederation from Lower Canada had identified as necessary for the preservation of the francophone language, religion, culture, and heritage. Letting provincial governments have the powers necessary to protect language, culture, and religion, was the key to Confederation and then the innovation of federalism was chosen for the new Dominion of Canada. Even though Canada was based on this idea of division of powers to allow for regional cultural autonomy, the federal and provincial governments have rejected similar devolution of powers to Aboriginal communities or provincehood for the Northern territories. The federal and provincial governments claim the population is too few and too dispersed to manage all these powers. And, of course, small provinces and Quebec do not want to start adding multiple provinces, beginning with three in the North, as their own relative influence would diminish.

But what about one province for all Aboriginal Peoples?

Aboriginal lands, including the three Northern territories, are legally held in reserve on behalf of Aboriginal Peoples. The federal government acts as trustee over the land, and this creates a rather distasteful paternalistic dimension to Aboriginal–Non-Aboriginal relations. What if our government simply takes all this land held in reserve and returns it to Aboriginals? Make all that land the 11th province of Canada.

The structure of government for this new province is unimportant and frankly not the business of the people who don’t live on this land. The constitutional change would be simpler than one would imagine. It would not require the unanimous consent of the provinces. According to the Constitution Act, 1982, the agreement of only seven provinces, representing the majority of the population, is needed for the federal parliament to create a new province. But it also states that this is “notwithstanding any other law or practice,” and for the federal parliament to take all remaining Aboriginal land and designate it the “final” province, given constitutionally entrenched treaty rights and federal jurisdiction over “Indians, and land reserved for Indians,” it may even be possible to do part of the change without provincial consent.

This change does not even have to significantly alter the existing structures of Aboriginal communities—unless, of course, they decide to alter them on their own once they have obtained provincehood. In many of the current provinces there are three levels of government managing provincial powers, namely the provincial government, regional governments and municipal governments. So, for example, the Government of Nunavut could continue as a regional government within the new Aboriginal province and the Sambaa K’e Dene Band could continue to operate similar to a municipal government, with authority delegated from the Aboriginal province. As the Aboriginal province would have all of the powers that Aboriginals have identified as central to the preservation of their languages, religions, and cultures, it can delegate powers as needed locally or act provincially as expedient.

With the exception of the creation of a provincial government, this is pretty close to the position the federal government has been taking vis-à-vis territorial governments and local band councils. The big change will be that in the future, instead of Aboriginals demanding from the federal government the right to handle their own affairs, they would be dealing with their own provincial government—a government they elect and that is accountable to them.

For those concerned about corruption within band councils, their own provincial government would regulate these matters and being concerned about how monies transferred to the local governments are handled, it would undoubtedly do so more effectively than the federal government, and without the racism or paternalistic interference. Equalization payments to the province would replace the now direct transfer to Aboriginals and their band councils, thus eliminating the demoralizing stigma of dependency. What is more, some of the Aboriginal land held in reserve is resource-rich, providing an independent source of revenue.

Critics of nationalism most strongly reject the idea of a province based on ethnicity. But based on its territory and its land base, the new 11th Province would not be exclusively Aboriginal. Many non-Aboriginals live on these lands and within the broader Aboriginal grouping there are First Nations, Inuit, and Métis, subdivided by hundreds of individual Aboriginal nations. This would be a civic nation like Quebec, and a province like any other, though the provincial leadership will likely be Aboriginal.

This largely Aboriginal province will be bigger in territory, richer in resources, and competitive in population size to the average Canadian province. It can negotiate with the more influential provinces, where many of its off-reserve citizens live or work, namely Alberta, B.C., Quebec, and Ontario. And, like the other civic nation of Quebec, its premier, by virtue of representing a cultural group that is in the minority across Canada, would have a powerful voice at the table of first ministers.

With provincehood would come an increase in Aboriginal members in the Senate and House of Commons. Aboriginal Peoples would finally be truly engaged in Canada’s political process—and this is essential for full citizenship and equality.

]]>

Peter Mansbridge interviewing Stephen Harper on CBC's the National, January 5, 2010. Screenshot from CBC broadcast.

It’s been a week now since the Prime Minister’s December 30 announcement that the house of commons would be prorogued until March 3, 2010. Peter Mansbridge’s toothless interview with the Prime Minister last night (first question: the underwear bomber? Seriously?) was disappointing. Mansbridge didn’t challenge the PM on anything of substance, and used that favourite tactic of TV talking heads everywhere, lots of “some would say…” and “you can’t read a newspaper editorial without hearing…” — the kind of non-interview interview where every question is attributed to someone (anyone!) other than the actual person sitting there asking the questions. It’s a shame, because we really needed a champion here, in the only opportunity to directly ask the PM these tough, crucial questions before a national audience.

The response to prorogue over the last week has run, as Dorothy Parker said, the emotional gamut from A to B: what I’ve seen, from grand media poobahs and my circle of friends alike, is various flavours of indignation, outrage, disappointment, fury, wrath, ennui, disapproval, disgruntlement, vexation, exasperation, umbrage, chagrin, and despondency. At least, that’s among the people who actually care, which is only about half the country, according to one disheartening poll.

Heather Mallick’s New Year’s Day article in the Guardian seems to express the sentiment in its most distilled form:

Instantly, we are a part-time democracy, a shabby diminished place packed with angry voiceless citizens whose votes have been rendered meaningless. […] Rage and shame are flowing on the internet because there is nowhere else for voters to turn. Even The Globe and Mail, Canada’s national and excessively staid newspaper, had a front-page editorial steaming with reproach. The Globe often leaves me frustrated, but I was moved when I read it and … did what exactly? I took a stand. I joined a Facebook group called Canadians Against Proroguing Parliament, an earnestly pathetic act that may be part of the reason our nation is so lessened on the first day of 2010.

The reason that sentiment rings so true for me is that a widespread response to the prorogue seems to have been “We have to do something” with a streak of “but nothing I can do will be enough.” There are thousands of people who joined that Facebook group who also simultaneously doubt the ability of that group to truly accomplish anything.

Jesse Hirsh published a blog post yesterday that also captures this zeitgeist of self-flagellation (though he’s ultimately more hopeful than Mallick’s take):

It’s hard not to snicker at the fact that joining a Facebook group to show opposition to something has become the ultimate cliché. While such a group does raise awareness and cross over into mainstream media with front page headlines, I am not alone in wondering whether it actually accomplishes anything.

Even worse, why is the alternative to this kind of virtual action doing absolutely nothing? It’s as if it has already become such strong orthodoxy that if you don’t join, or even worse complain, you’re regarded as a nay-sayer and are also responsible for providing alternatives.

We want to do something, but there’s no consensus on what to do, so anything we do in the meantime—calling our MPs, joining a Facebook group, emailing the Governor General—gets devalued because it’s not the One Big Thing that’s going to fix everything. I recognize the feeling because I feel it myself, even as I know it to be self-defeating.

]]>

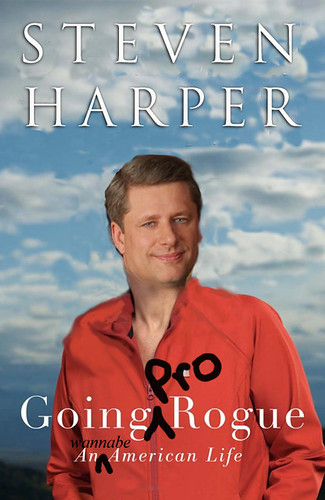

Sarah Palin/Stephen Harper mashup, courtesy Wayne MacPhail

This morning several news sources reported that Prime Minister Stephen Harper planned to prorogue parliament until March 3. This story is a bit of a moving target today, so this is just a quick post to collect some of the thought we’ve seen bubbling around the web today:

The PMO’s official announcement/non-announcement is now out.

CBC Inside Politics blogger Kady O’Malley was initially skeptical that the call would come today, but has been hard at it the rest of the day and made several posts.

Maclean’s columnist Andrew Coyne compared the move to King Charles I dissolving the English parliament in 1640.

Toronto Star columnist Haroon Siddiqui said that Harper was behaving like an “Elected dictator.”

As of this moment, it’s not clear whether parliament is actually prorogued. The Governor General hasn’t signed the proclamation making it so, reportedly, and the PMO is mum on the issue, as John Geddes writes about, again for Maclean’s.

NDP house leader Libby Davies tweeted this afternoon that it’s a done deal.

Liberal MP Hedy Fry tweeted that the move was an “insult to democracy”

We’re following more on the whole fiasco with Wayne MacPhail’s twitter hashtag, #notoprorogue

Update, 15:48: The National Post columnists have weighed in, saying a) everything’s fine, and b) Parliament must be prorogued so the senate can, like, settle in, or something.

Update, 15:58: Our friends at Rabble are hosting a discussion about the proroguement in their Babble forums.

Update, 16:09: John Geddes’ take on PMO Spokesperson Dimitri Soudas’s press briefing earlier this afternoon sheds a little light on the talking points we’re hearing. It includes this statement from Soudas, about the Afghan detainee investigation:

“They are looking at an issue where it is old news,” he said, adding, “And we’re going to continue focusing on the economy.” Obviously, keeping the issue alive through January and February is now a key challenge facing Liberal Leader Michael Ignatieff.

Please feel free to add more info in the comments.

]]>